By Aaron Keebaugh

Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan managed to keep the micro-opera’s crazed figure sympathetic as he blurred the lines between reality and delusion.

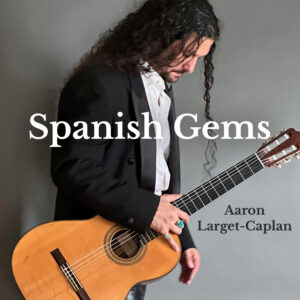

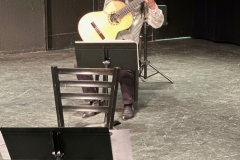

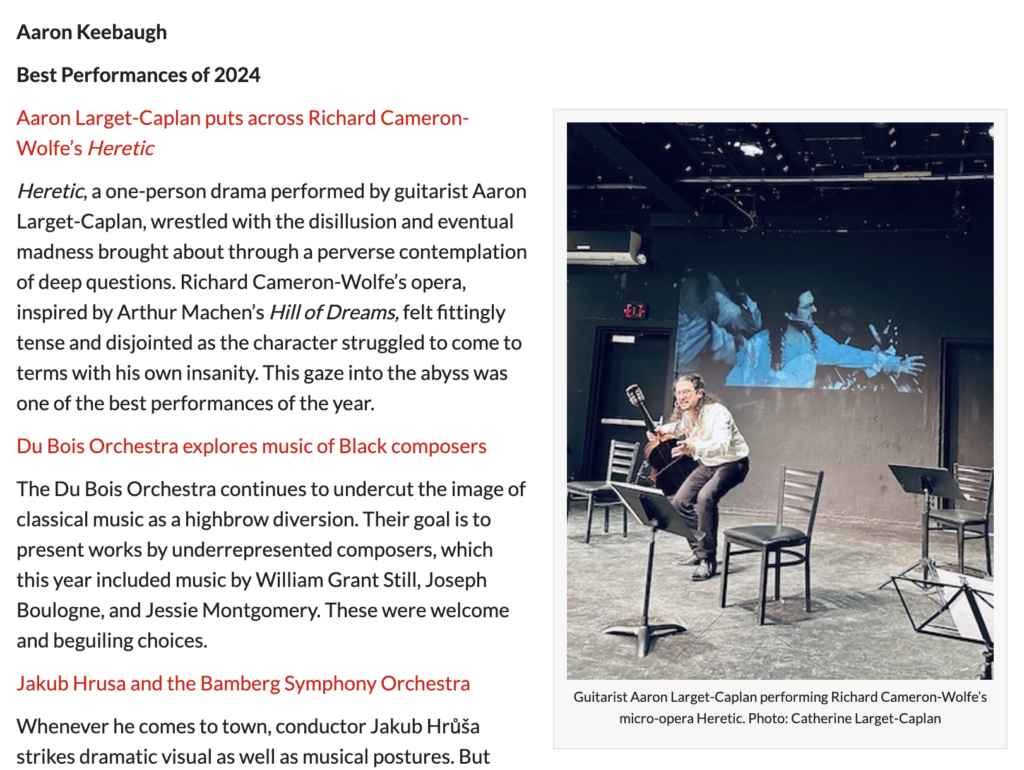

Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan performing Richard Cameron-Wolfe’s micro-opera Heretic. Photo: Catherine Larget-Caplan

“The secret of life is learning to live with interesting questions,” Richard Cameron-Wolfe said during the post-performance talkback following the American premiere of his micro-opera Heretic at Salem State’s Callan Studio Theater last Friday. The performer and composer had made good on that claim in the compelling resonance of his composition.

In this one-person drama, the protagonist, accompanying himself on guitar, wrestles with bewildering, irresolvable issues that lead to disillusion and eventual madness. Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan managed to keep the crazed figure sympathetic as he blurred the lines between reality and delusion.

Given its challenging psychological extremes, the opera cruises through a wide range of emotions in its taut 15 minutes. Drawing on jagged musical textures as well as a disjointed monologue, the score is a journey toward a sharp and shattering gaze into the abyss. The guitarist is both hero and antihero — steeped in the craziness he is gallantly struggling to overcome, this is a journey into coming to terms with insanity.

Inspired by British writer Arthur Machen’s semi-autobiographical 1907 novel The Hill of Dreams, Heretic starts off by placing its central figure in an almost nonsensical predicament. Larget-Caplan plays a character lost in a mental fog. He ambled onto the stage, shifting his gaze about nervously. He then sat down and tore through a jarring phrase that fell somewhere between the soundscapes of Iannis Xenakis and Steve Reich. Vocal utterances entered the fray, and words were slowly formed — language which was interrupted by more waves of violent dissonance. Though it was composed with Cameron-Wolfe’s usual mathematical precision, the music in Heretic can sound personal and harrowing. The piece places listeners into Machen’s dark, dreamy world, where the overwrought senses are finding it harder and hard to discern what is true.

But, while this was an unapologetic descent into mental oblivion, Larget-Caplan’s character is no Parsifalian fool. The man has his semi-lucid moments, articulating a cultural critique in which he blamed himself and others for creating a civilization that has no love for beauty and purity. Our ideals of art, he reasoned, were no longer goals for the imagination to reach — they were artifacts of what we have lost. As he made these scathing observations, the guitarist unleashed another barrage of sound — like an atonal heavy metal riff — that framed his points with an ironic levity.

Here was a man who was driving himself to the end of his tether. Larget-Caplan’s nervous and angular movements suggested the angst of a mind that couldn’t stop churning, couldn’t stop torturing itself. At one point, the guitarist angrily bolted to the rear curtain as if to abandon his mission to think, only to be sucked back in. Heretic ends in a spirit of disquiet — with mumbled words accompanied by the sound of a guitar purposely falling out of tune. The man’s dilemma is inescapable. Caught up in a vicious cycle of grand accusations and self-absorption, he boldly embraces his disheveled mental state, all pain and no illumination.

These manic swings were well-served by Friday’s minimalist staging. Chairs were arranged in cross patterns — as much a symbol of confusion as a pragmatic choice for Larget-Caplan’s performance. Michael Harvey’s lighting and video projections conveyed an eerie aura; Jerry L. Johnson’s swift and economical stage directions never let the solipsistic action lag. The wild thorns of Cameron-Wolf’s score were well served by Larget-Caplan, whose bold and energetic presence underscored his talents as a musician and actor.

The other pieces on his hour-long program were also dedicated to introspection. Keigo Fujii’s The Legend of Hagoromo relayed a Japanese legend with cinematic flair. It is a narrative of a woman who is whisked away to heaven, where she mourns the absence of her husband and son. Her tears water a flower on earth that grows toward paradise. Father and son climb up it to visit her. Fujii’s music colorfully conveys the sadness and joys of this metaphoric meditation on death, loss, and hoped-for reunion. Larget-Caplan played the piece like the fanciful love letter it is: warm and reflective, yet coursing with frequent flamenco-like verve.

John Cage’s In a Landscape embraces greater ambiance. Larget-Caplan’s arrangement of the piano original — inspired by Erik Satie — makes use of Campanella-style playing. Harmonics are meant to ring over the regularly fingered melodic line. The difficulty in executing such complicated effects are considerable, and the guitarist’s arrangement didn’t fit snugly under the fingers. The upshot is that at times Larget-Caplan’s performance felt labored and mechanical, lacking the resonance, the distant glow, that marks the original conception.

Larget-Caplan’s arrangement of Bach’s Prelude in C Major and Vineet Shende’s Carnatic Prelude No. 1 proved more successful. His generous rubato in the Bach allowed him to revel in every shift in harmony. In the Shende — a view of Bach by way of Indian classical music — he unspooled melodies and rhythmic flourishes over drone-like resonances. It was a splendid exercise in singing tone and alert sensitivity.

When taking his bows, Larget-Caplan gestured to his guitar, happy to share the limelight with an instrument that had done its job well. Still, modesty aside, the strengths of these performances came down to Larget-Caplan, a musician of fluent technique and dramatic verve.

Aaron Keebaugh has been a classical music critic in Boston since 2012. His work has been featured in the Musical Times, Corymbus, Boston Classical Review, Early Music America, and BBC Radio 3. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in both Danvers and Lynn.

Click here or the link above to read the complete review

Click here or the link above to read the complete review