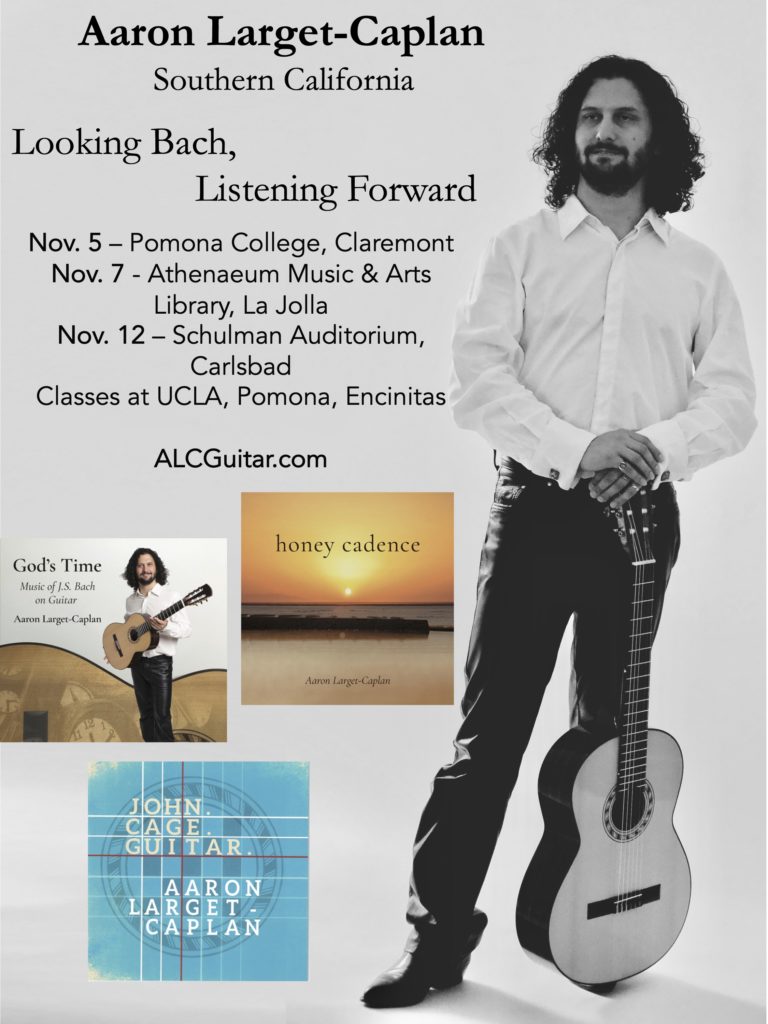

God’s Time—Music of J.S. Bach on Guitar is another in a series of superb recordings from Aaron Larget-Caplan. Here, Larget-Caplan performs his own transcriptions of Bach’s music. In my extended interview with Aaron Larget-Caplan, the guitarist describes his intensive exploration of Bach, and pays tribute to the musicians who have served the Baroque master so well. In that interview, Larget-Caplan’s reverence for, and affinity with Bach’s music are clear. And those elements are affirmed both in Larget-Caplan’s superb transcriptions and his poetic renditions. All of the transcriptions preserve the integrity and beauty of Bach’s original compositions.

In our interview, Larget-Caplan quotes organist/harpsichordist Peter Sykes, who “advised that transcriptions should sound as if they were written for the instrument.” This, Larget-Caplan achieves as well, in sterling fashion. And the rightness of his transcriptions are affirmed in performances that bear Larget-Caplan’s characteristic gorgeous tonal quality, crystal-clear articulation, and poetic phrasing. Larget-Caplan’s delineation of Bach’s contrapuntal writing is remarkable for its balance of precision and supple musicality. And in his fiery rendition of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy, Larget-Caplan communicates his view of the work as a precursor to the Sturm und Drang movement. The gorgeous recorded sound does full justice to Larget-Caplan’s artistry. A splendid release.

Ken Meltzer, Fanfare

Five stars: Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan’s exquisite transcriptions of Bach

Five stars: Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan’s exquisite transcriptions of Bach

Interview with Aaron Larget-Caplan by Ken Meltzer, Fanfare

God’s Time—Music of J.S. Bach on Guitar, presents arrangements and performances by Aaron Larget-Caplan. I spoke with Larget-Caplan about his lifelong exploration of Bach, the composer’s legendary interpreters, the art of transcription, and the significance of the repertoire included in God’s Time.

Your liner notes for God’s Time – Music of J.S. Bach on Guitar contain some fascinating comments that I would love to pursue further. For example: “There are many interpretations of Bach’s music by renowned artists to explore and ideas to internalize, which early in my career I found musically overwhelming.” Tell us about some of those artists, and why they inspired the profound reaction you describe.

The recordings of the major 20th-century masters were so full of personal character and technical mastery with each bearing the stamp of the performer, the space, and the label. I’m thinking of Gould and Richter, Heifetz, Landowska, Rostropovich, and Casals. They did things that many frown upon now, but even the approach to how the instruments were recorded was unique with the labels trying to be independent of each other. These performances still make me excited.

As I explored more and more, I discovered pianists such as Samuel Feinberg and William Kapell, both of whom were technical masters. I fell for Kapell through his Prokofiev recordings.

Living in Boston, violinists Rachel Podger, Christian Tetzlaff, Christoph Poppen are not unheard-of names. Each quite unique from the other, they shed light on ornamentation, variation of tempi, and lyricism.

I believe every guitarist goes through a harpsichord phase. Mine began with Landowska, and then the NEC early music department under John Gibbons. The wonderful Peter Sykes has deservingly placed his stamp on Boston and I’m grateful to hear him perform. Searching for Lute-harpsichord albums, I found the lovely collection by Robert Hill. Informative notes and playing, but hearing such works on early keyboards, which have different mechanisms and action speed then the modern day piano also gives the work a human touch. Gould is great, but fast is not always a choice I agree with.

Regarding the guitar, I fell in love with the early recordings of Maria Luisa Anido and Luise Walker for their use of color, rubato, and unbelievable technical abilities. Segovia’s Cello Suite No. 1 Prelude was, and still is, mind blowing. The structure and drama of Julian Bream’s Lute suites, the clarity of the Assad Duo, Paul Galbtraith’s silky touch, and the inventiveness of David Leisner’s ornamentation all played influential roles in what I do today.

At the end of the day, I can’t say any of these are right or wrong. I believe it is up to the artist to fully invest themselves in the music. I am not Julian Bream, nor should I be. To have Music in Life and a Life in Music means I must be me in every note. That said, stealing is most welcome.

You further reveal: “I took a break from programming (Bach) to allow time to study his music through unknown masters on various instruments, read more about his life, and further explore the place of music in society through writings of John Cage, Toru Takemitsu, Hazarat Inyat Kahn, and others.” Would you be willing to tell us more about this path of exploration?

Society’s relationship with music has changed over the course of time. What was once sacred and only heard in a church or private court is now background music or filler for video games. Since my first album was released in 2006, the practice of hearing and experiencing music has completely changed, and that’s without thinking about Covid.

For a short time in 2nd half of the 20th century, the advent of recorded music allowed some musicians to believe that recordings would be enough to give up live performance. For some this was great, while others disagreed. Though it wasn’t an option for me, I do believe the relationship between artist and audience to be sacred. I worked to make the recording intimate and as if the listener had very good seats in a beautiful space.

Books on the life of Bach and interpreting his music that I found inspiring:

- Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven by John Eliot Gardiner

- Interpreting Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier: A Performer’s Discourse of Method by Ralph Kirkpatrick

- Bach Interpretation: Articulation Marks in Primary Sources of J. S. Bach by John Butt

- Bach: Expanded Edition by Little, Meredith, Jenne, Natalie

- Bach by Frederick Neumann

- The Fencing Master, About Mrs. Anna Magdalena Bach’s Autograph Copy of the 6 Suites for Violoncello Solo senza Basso of Johann Sebastian Bach by Anner Bylsma

Books on performing and the place of music in society:

- Glenn Gould Reader by Glenn Gould

- Charm and Speed: Virtuosity in the Performing Arts by Vernon Alfred Howard

- Confronting Silence by Toru Takemitsu

- Silence by John Cage

- The Music of Life and other titles by Hazrat Inyat Kahn

Please tell us a bit more about your involvement with John Cage, and in particular, your arrangements and recordings of his music.

What started as a wouldn’t-this-sound-cool type of project, became a recording and publishing endeavor far beyond what I imagined. In 2013, I arranged the piano part of Cage’s ‘Six Melodies’ for violin and guitar and performed it as part of my faculty recital at the Boston Conservatory with violinist Sharan Leventhal. Composer and violinist Thomas L. Read loved it and encouraged me to reach out to Edition Peters. I did.

They published the score in 2015 and it sold well enough for them to ask for a set of solos. In 2018 they published seven solos under ‘Piano Music for Guitar,’ and in September 2022 Bacchanale for prepared guitar duo. An album of all of them, John. Cage. Guitar. (Stone Records) came out in 2018.

In January 2020, I was Musician in Residence for a month at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Canada where I began working on two more large arrangements, and I returned the project in May 2022 with a weeklong residency in Clinton, New York at the Kirkland Arts Center.

The music has been very well received and the director of the John Cage Trust, Laura Kuhn, and host of ‘All Things Cage’ has had me on multiple times.

Cage’s music introduced me to many wonderful artists and expanded my understanding of the mid-20th century American music and art scene, but more importantly, the reaction of audience members to this music has been overwhelmingly positive.

Many musicians’ only relationship to Cage’s music comes from his later creations, so they are surprised to learn of the lyricism and beauty he composed. General audience actually love it.

Tell us about the title you chose for the new Bach CD (God’s Time), and its significance to the project.

As I mention in the liner note, pianist Seymour Bernstein introduced me to the work ‘Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit’ (God’s Time is the Very Best Time), BWV106, and asked me to arrange it for guitar. I knew right away it was a “keeper” and the title of the album had to be ‘God’s Time.’

As a musician knows, sometimes we play Bach and other times Bach plays us. It’s not on our time…

God’s Time features your transcriptions of various works Bach originally composed for keyboard. Bach’s music has long been the subject of transcriptions. Bach himself often repurposed his music for different pieces and performing forces. What is it about Bach’s music that makes it so attractive (and effective) for transcription?

The fact we don’t know much about Bach as a person, exactly how his music was played, except for an occasional tempo and dynamic marking, the general lack of direction, how it actually sounded at the time, and how it was received, allows for a great amount of freedom; the music can be shaped to reflect our own personal tastes.

I grew up hearing the amazing music played on a piano, not a period instrument, so I have accepted such changes from the start.

The variation and steadfast belief musicians have for their own interpretation made me adapt a little joke for Bach: If two musicians on a deserted island had to agree on how to interpret a Bach prelude, there would be three versions: one for each of them, and one they both dislike.

As a guitarist, the lack of original works by the famous European composers, made transcription for the guitar a cornerstone of the 20th century repertoire: Albéniz, Granados, Scarlatti, Piazzolla, and Handel. Today it is not uncommon to hear Mussorgsky or Cage on one guitar and Beethoven on two. It almost feels the common practice of transcribing popular music for various instruments that existed pre-recording era is starting to return.

My general belief: as long as music is being played and introduced to society it is a good thing.

What are some of your favorite Bach transcriptions by other artists, and what qualities in them do you find particularly compelling?

By far the most influential are those by Ferruccio Busoni. I know I heard the Bach-Busoni Chaconne prior to hearing it on violin or guitar.

Researching the album, I found he did quite a few other adjustments to Bach. I almost included Busoni’s version of the Little Fugue in C Minor, BWV 961 (played in D Minor), which has three more measures.

For a time, I had a small obsession with searching out various versions of the Chaconne, including the Brahms for piano left hand, Busoni’s, electric keyboard, multiple for cello, viola, harp, and even the choral-violin version of The Hilliard Ensemble & Christoph Poppen.

The work of the guitar duos, Presti and Lagoya, Assad Brothers and the Abreu Brothers cannot be overstated. The clarity of their playing and inventiveness of ornamentation are breathtaking. I also have a love for mid-20th century solo guitar transcriptions with their lovely colors and romantic rubato additions.

What are your thoughts on Leopold Stokowski’s kaleidoscopic orchestral transcriptions of Bach?

Love them. Bach pushed the instruments and voices at his disposal to their limits, so I would have a hard time believing he would not have done similarly with a 20th century orchestra.

What are your goals and challenges when transcribing Bach’s compositions?

Many years ago, I spoke about with organist/harpsichordist Peter Sykes, who famously transcribed Gustav Holst’s ‘The Planets’. He advised that transcriptions should sound as if they were written for the instrument. I think this to be wise advice.

With the Six Small Preludes and A Little Fugue, I wanted the works to sound as if they were written for guitar, while also acknowledging the keyboard lesson aspects for those who know them. For instance, though it was extremely difficult, I wanted to make sure ornaments in the bass voice of Prelude in C Major, BWV 924 were clear, and the tempo in Prelude in D Minor, BWV 962 was proper to feel the hemiolas, and the bass articulation in Prelude in C Minor, BWV 999 was somewhat close to the actual notation.

The Prelude and ‘Fiddle’ Fugue presented a whole new set of challenges as there are different versions for violin, organ, and lute. Julian Bream famously made his transcription from the lute and violin.

Again, Peter Sykes urged me to check out the organ version in D Minor, BWV 539, which includes a prelude. I was intrigued right away, as I always disliked how the lute version lacked a prelude, and when I read through the organ version, I knew it would be perfect on guitar.

In the fugue I saw so many dissonant notes that were playable on guitar, so I slowly started adding them to my Segovia & Tárrega scores and after a week or two I was writing out my own “new” version.

In your liner notes, you address the issue of retaining the keys of the original Bach works.

Though speculation of the spiritual meaning of keys and their effects on the listener, I do believe Bach was fully aware of the symbolism of each key. He doesn’t come across as a composer who left things to chance.

As a guitarist, I wanted to try to make sure that the album was not just in the standard ‘guitar keys’ (E, A, D). Besides the use of the Capo, there are three tunings on the album: Standard, drop D, and G (5-G, 6-D).

Though Bach changed the key to multiple compositions to suit the instrument (see “fiddle” Fugue BWV 539/1000/1001), I did want to keep the original key when possible. For ‘God’s Time…’ and the Prelude in E Flat Minor, WTC I, BWV 853, I was able to keep the original keys of E Flat Minor and E Flat major by tuning my lowest string (6) from E/mi to D/re and then adding a Capo on the first fret.

Tell us about the repertoire on God’s Time, and why you chose it for transcription and performance.

Prelude, Fugue, Allegro in E Flat Major, BWV 998 (played in D Major) • A unique work that stands out from the lute suites in its lyricism, construction, and flexibility of interpretation. The technical approachability of the prelude is countered by the daunting six-minute, three-part and three-voice fugue of movement two. The binary allegro looks straightforward but asks many questions of the interpreter. The symbolism and mathematical relations of the movements inspire, and the fact that each movement has some sort of repetition invites the performer to ornament, which I do.

ornament, which I do.

Prelude in C Major, WTC I, BWV 846 • Part of my repertoire for years, it was the right time to record it.

Prelude & Fiddle Fugue, BWV 539/1000 • Epic and see above.

God’s Time is the Very Best Time, BWV 106 • So many of us have experienced loss over the last two years, that it seemed like the right piece for the time.

Chromatic Fantasy in D Minor, BWV 903 • One of my favorite instrumental solos of Bach for its completely unique place in repertoire. The toccata opening, the recitative middle section with sudden flourishes, and the descending diminished chords of the closing, the knocking of death, only to finish on the warmest of D Major chords. Such a range of emotions that it could easily be considered a Sturm und Drang work a century later. Maybe it was foreshadowing the movement… Regardless, a masterpiece!

Prelude in E Flat Minor, WTC I, BWV 853 • I heard Richter’s performance of this prelude and knew I would need to make a version for guitar. The pacing, the floating melody that climbs and falls, the oscillating minor 2nds, the dotted rhythms, and warmth of the last four bars. Just magical.

Six Small Preludes and A Little Fugue • I am extremely proud of these transcriptions. From a pedological standpoint for guitar, they are wonderful additions to the repertoire that allow students to play smaller works by Bach that can be steppingstones to larger works. Musically, they contain a plethora of emotions that require a level of technical mastery but are also open enough that various tempos can be chosen and quite satisfying unto themselves.

In one of your transcriptions, that of the BWV 999 Prelude, you incorporate a bit of another Bach piece.

Yes, I have never been content with the Little Prelude in C Minor, BWV 999 ending on the dominant. It is accepted as that’s-the-way-it-is, but not for me. I was working on a transcription of Prelude 3 in C Major, WTC II, BWV 872, which I found to have a similar arpeggio motif and that also ends on the dominant before a coda finishes the piece. I stole the coda from BWV 872, transposed it to the dominant of D Minor (A Major), and added it to the end of BWV 999 as a new Coda. It is not perfect, but I think it follows the line of Busoni fixing the Prelude in C Minor, BWV 961, and a lot of fun to perform.

Some of the included Bach compositions have been previously transcribed by others. Did that impact your approach in your own transcriptions of the works?

Quite a bit and especially with the Prelude, Fugue, Allegro, BWV 998.

My instructors at the New England Conservatory, David Leisner and Eliot Fisk, are both well known for their transcriptions, so it seems very natural to make my own.

Leisner also expected his students to add ornament. His Bach recording is inspiring in this respect.

Are there other Bach compositions you’d like to transcribe?

Quite a few!

On another subject: In the Nov/Dec 2021 issue of Fanfare (45:2), I had the pleasure of reviewing Vols. 2 and 3 (Stone Records) of you performing works from your The New Lullaby Project. Tell us about that project and the recordings.

The New Lullaby Project began in 2007 to bridge the chasm of fear composers have for writing for the guitar and audiences towards listening to contemporary music. Since then, over 65 composers from 10 countries have had their new lullabies premiered, with number 71 receiving its premiere in October 2022.

The first album, New Lullaby, came out in 2010, followed by volumes 2 and 3 (Nights Transfigured and Drifting) in 2020 and 2021 with 46 having been recorded to date.

In 2020, in partnership with the American Composers Alliance, we published the first anthology of scores, Nights Transfigured, which earned multiple Revere Awards from the Music Publishers Association of the United States. Volume 2, Hushed, was published in 2021.

More recordings and publications are in the works.

While we’re on the subject of your other recordings, Colin Clarke (Fanfare 46:1, Sept/Oct 2022) reviewed honey cadence, a collection of your own compositions for guitar. Take us on a brief tour of this endeavor, please!

honey cadence explores some of my favorite aspects of the guitar: timbre, harmonics, string bends, and having the same pitch in multiple places on the instrument. Each title has something to do with a musical direction: cadence, moving, nuance, anticipation, play. Musically they are influenced by John Cage, bits of Bach, and Villa-Lobos, with nods to Ravel and even Queen. The latter weren’t necessarily conscious, but I hear them now.

I’m very proud of finally entering this new artistic realm, and the response has been outstanding with over 700K streams since its release in April 2022!

What future endeavors are on the horizon?

- ACA publication of honey cadence scores.

- Edition Peters publication of a solo by Alan Hovhaness.

- A guitar and electronics project, which has heard premieres by Tom Flaherty, Lou Bunk, and Lainie Fefferman. Videos online.

- A large work by Daniel Felsenfeld, his first guitar solo.

- New Lullaby Project premieres, recording, and publishing.

- A micro-opera by Richard Cameron-Wolfe.

- And a great project: Carnatic Preludes, After J.S. Bach with composer Vineet Shende (Bowdoin College). Shende re-imagines WTC preludes as if Bach were from South India and we pair them to my own transcriptions of Bach’s originals. We started in 2017 and have only a couple left.

The horizon is full of music!

Aaron Larget-Caplan’s website: https://alcguitar.com

BACH (arr. Larget-Caplan) Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro in E-flat, BWV998. The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1: Prelude No. 1 in C, BWV846; Prelude No. 8 in e-flat, BWV853. Prelude and Fugue in d, “Fiddle” BWV539-1000. God’s Time is the

Very Best Time, “Actus tragicus”, BWV106. Chromatic Fantasy in d, BWV903. Twelve Little Preludes: in C, BWV924; in d, BWV926; in g, BWV930; in c, BWV999-872. Fugue in c, BWV961. Six Little Preludes: in c, BWV 934. Five Little Preludes: in C, BWV939 • Aaron Larget-Caplan (gtr) • Tiger Turn (888-09) • (Streaming audio: 49:02)